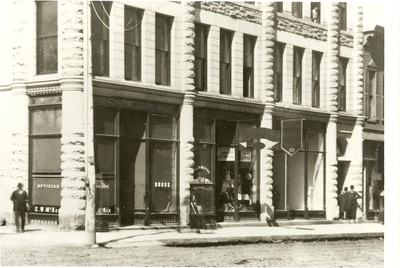

SCHMITZ BLOCK

c. 1888

926-930 S. Calhoun Street

The Schmitz Block is one of Fort Wayne’s most widely-recognized historic buildings.

Catalyst Marketing Design currently occupies the street level of this building, with the upper floors housing 18 residential condominiums.

The exterior of the building showcases elaborate work by the artisans involved in its construction, including limestone piers that stand the full height of the building and intricate carvings across the facade. A feature that is rarely noticed by the passerby is a unique cornice with grotesques (whimsical figures or caricatures), chimaeras (pronounced kimira – fire-breathing monsters), a lion’s head and other detailed work. Each is handcrafted and no two are alike.

c. 1888

926-930 S. Calhoun Street

The Schmitz Block is one of Fort Wayne’s most widely-recognized historic buildings.

Catalyst Marketing Design currently occupies the street level of this building, with the upper floors housing 18 residential condominiums.

The exterior of the building showcases elaborate work by the artisans involved in its construction, including limestone piers that stand the full height of the building and intricate carvings across the facade. A feature that is rarely noticed by the passerby is a unique cornice with grotesques (whimsical figures or caricatures), chimaeras (pronounced kimira – fire-breathing monsters), a lion’s head and other detailed work. Each is handcrafted and no two are alike.

The attention to detail extends inside. The upper floors were originally used as professional offices and the feel of affluence continues there, with marble on the corridor walls and terrazzo on the floor. When the upper floors were converted to living space, the corridors were kept intact, including all of the original doors with transoms. Due to noise, carpet was installed over the terazzo, but it does spill into the entryway of some of the residential condominiums and one owner has restored his small patch of the flooring to its former beauty. The tin ceiling has also been preserved in the first floor space.

The Schmitz Block was erected by Henrietta Schmitz, as a monument to her deceased husband, Dr. Charles Schmitz. Dr.

Schmitz was one of the city’s first physicians. He and his wife were German immigrants who came to Fort Wayne in 1837. In

1839, Dr. Schmitz purchased the entire quarter block and built his family’s residence here in 1840. In 1866 he subdivided

the site and began to build storefronts on it as rental properties. Within a year of her husband’s death, and despite

warnings by friends that the land was too far to the south of downtown to support such a large commercial building

profitably, Mrs. Schmitz erected the structure that is now part of Midtowne Crossing. The Schmitz children continued to

own most of the quarter block until 1912, when they sold it to William F. Noll (see Blackstone Building).

A variety of commercial tenants used the stores and offices in what was then renamed the Noll Block. Hutner’s Paris (see

Hutner Building) used parts of the upper floors after 1947. Nobbson, a women’s clothing store, which left for the suburbs

in 1979, was the building’s last tenant prior to the rehab for Midtowne Crossing in the late 1980s.

During the conversion of the Schmitz Block to its present use, most of the historic aspects were preserved. However,

restoration of this building was no small task because layers of “updating” done throughout the mid-1900s had to be

removed to reveal the original street facade. Today, the Schmitz Block is as glorious as ever and we are proud to have it

as part of Midtowne Crossing.

The Schmitz Block is primarily of local architectural significance as one of the largest existing local commercial examples of

the Richardsonian Romanesque style; it is also one of the few remaining works of Frank B. Kendrick, a local architect.

Though the Richardsonian mode provided most of the architectural vocabulary popular for Fort Wayne commercial

structures of the late nineteenth century, few of them were built with facades made entirely of cut stone, and of those,

fewer still have survived to this day. Among the largest examples, other than the Schmitz Block, were the Pixley-Long Block

(1886, Wing & Mahurin, architects; demolished 1929) and the Odd Fellows Building (1890, Frank Kendrick, architect,

demolished 1949). The only other commercial design by Kendrick to survive is his 1891 Louis Mohr Block, a two story

building located at 119 W. Wayne Street. Kendrick was a native of Philadelphia; he began his architectural career in that

city in the office of Bruce Price, in 1869. By 1879, Kendrick had moved west to Fort Wayne after stays in Lancaster,

Pennsylvania, and at Salem and Springfield in Ohio. In 1880, he started a contracting firm with Alfred Shrimpton; after 1888,

Kendrick resumed his architectural practice. Though he returned to Ohio briefly in 1889, Kendrick had returned to Fort

Wayne by 1891. He apparently left Fort Wayne permanently for Crown Point, Indiana about 1901. During his years in Fort

Wayne, the city’s architectural scene was dominated by the firm Wing and Mahurin; Kendrick is notable as the only other

local architect, especially during the late 1880s and early 1890s, whose commercial work matched the scale and

sophistication of that other firm.

History and architectural information were taken from the National Historic Register nomination written by Craig Leonard in

1987. It was updated through our own research and with assistance from Don Orban.

The Schmitz Block was added to the National Historic Register in 1988 and to the Local Historic Register in 1989.

THE SMOKE STACK

One cannot walk into the courtyard without noticing the large, square smoke stack that extends the height of the

surrounding buildings. Visitors and residents alike are always curious about it.

Where the courtyard now sits there was an underground boiler room that fed heat to the Schmitz Block and the smoke

stack was part of that heating system.

The structure was deemed to be “historically significant” and so, required saving. Tons of concrete and tens of thousands

of dollars went into preserving the smoke stack. No doubt, it will stand strong and continue to provide a subject of

speculation for generations to come.

The Schmitz Block was erected by Henrietta Schmitz, as a monument to her deceased husband, Dr. Charles Schmitz. Dr.

Schmitz was one of the city’s first physicians. He and his wife were German immigrants who came to Fort Wayne in 1837. In

1839, Dr. Schmitz purchased the entire quarter block and built his family’s residence here in 1840. In 1866 he subdivided

the site and began to build storefronts on it as rental properties. Within a year of her husband’s death, and despite

warnings by friends that the land was too far to the south of downtown to support such a large commercial building

profitably, Mrs. Schmitz erected the structure that is now part of Midtowne Crossing. The Schmitz children continued to

own most of the quarter block until 1912, when they sold it to William F. Noll (see Blackstone Building).

A variety of commercial tenants used the stores and offices in what was then renamed the Noll Block. Hutner’s Paris (see

Hutner Building) used parts of the upper floors after 1947. Nobbson, a women’s clothing store, which left for the suburbs

in 1979, was the building’s last tenant prior to the rehab for Midtowne Crossing in the late 1980s.

During the conversion of the Schmitz Block to its present use, most of the historic aspects were preserved. However,

restoration of this building was no small task because layers of “updating” done throughout the mid-1900s had to be

removed to reveal the original street facade. Today, the Schmitz Block is as glorious as ever and we are proud to have it

as part of Midtowne Crossing.

The Schmitz Block is primarily of local architectural significance as one of the largest existing local commercial examples of

the Richardsonian Romanesque style; it is also one of the few remaining works of Frank B. Kendrick, a local architect.

Though the Richardsonian mode provided most of the architectural vocabulary popular for Fort Wayne commercial

structures of the late nineteenth century, few of them were built with facades made entirely of cut stone, and of those,

fewer still have survived to this day. Among the largest examples, other than the Schmitz Block, were the Pixley-Long Block

(1886, Wing & Mahurin, architects; demolished 1929) and the Odd Fellows Building (1890, Frank Kendrick, architect,

demolished 1949). The only other commercial design by Kendrick to survive is his 1891 Louis Mohr Block, a two story

building located at 119 W. Wayne Street. Kendrick was a native of Philadelphia; he began his architectural career in that

city in the office of Bruce Price, in 1869. By 1879, Kendrick had moved west to Fort Wayne after stays in Lancaster,

Pennsylvania, and at Salem and Springfield in Ohio. In 1880, he started a contracting firm with Alfred Shrimpton; after 1888,

Kendrick resumed his architectural practice. Though he returned to Ohio briefly in 1889, Kendrick had returned to Fort

Wayne by 1891. He apparently left Fort Wayne permanently for Crown Point, Indiana about 1901. During his years in Fort

Wayne, the city’s architectural scene was dominated by the firm Wing and Mahurin; Kendrick is notable as the only other

local architect, especially during the late 1880s and early 1890s, whose commercial work matched the scale and

sophistication of that other firm.

History and architectural information were taken from the National Historic Register nomination written by Craig Leonard in

1987. It was updated through our own research and with assistance from Don Orban.

The Schmitz Block was added to the National Historic Register in 1988 and to the Local Historic Register in 1989.

THE SMOKE STACK

One cannot walk into the courtyard without noticing the large, square smoke stack that extends the height of the

surrounding buildings. Visitors and residents alike are always curious about it.

Where the courtyard now sits there was an underground boiler room that fed heat to the Schmitz Block and the smoke

stack was part of that heating system.

The structure was deemed to be “historically significant” and so, required saving. Tons of concrete and tens of thousands

of dollars went into preserving the smoke stack. No doubt, it will stand strong and continue to provide a subject of

speculation for generations to come.